Meet the family reaching across cultures with music

In celebration of Racial Harmony, we speak with the Tan family - who plays Indian classical music - about the role of music in connecting cultures and traditions.

- 19 Jul 2023

Kenny Tan Thiam Teck’s love for the sitar has been life changing for him and his family.

“I want to play the music as it is, as pure as possible. When people listen to me play, I’d like them to think it’s a maestro playing. My race wouldn’t matter,” says Kenny Tan Thiam Teck, sitting cross-legged in front of several rows of sitars.

The 65-year-old Chinese Singaporean smiles as he tells Kaya how these Indian classical string instruments changed his life. Music is his passion and a means of reaching across cultures. Indian music would see him convert to Hinduism, take a new name (Krsna Laila Dasa), spend 10 years in India, become a vegetarian, pick up yoga and even study under the Sitar legend Ravi Shankar.

Even so, and even after decades of dedication to his craft, some people are surprised to see him performing Indian music.

“Being a non-Indian, people would say, it’s okay. What you’re playing is good enough, even some Indians can’t play like that. If you make a mistake, it’s okay, because you’re not even an Indian,” he says.

His sons have followed in his footsteps, becoming accomplished sitar and tabla players and in the process shaking hands with Indian culture.

The 65-year-old Chinese Singaporean smiles as he tells Kaya how these Indian classical string instruments changed his life. Music is his passion and a means of reaching across cultures. Indian music would see him convert to Hinduism, take a new name (Krsna Laila Dasa), spend 10 years in India, become a vegetarian, pick up yoga and even study under the Sitar legend Ravi Shankar.

Even so, and even after decades of dedication to his craft, some people are surprised to see him performing Indian music.

“Being a non-Indian, people would say, it’s okay. What you’re playing is good enough, even some Indians can’t play like that. If you make a mistake, it’s okay, because you’re not even an Indian,” he says.

His sons have followed in his footsteps, becoming accomplished sitar and tabla players and in the process shaking hands with Indian culture.

Musical expression requires cultural understanding

Kenny’s love affair with the Sitar started one morning in the 1980s, when he heard Sitar master Ravi Shankar on the radio. Completely mesmerised, Kenny resolved to learn the instrument, and to study under Ravi Shankar himself.

At that time, he was playing with Singapore Broadcasting Corporation as the house band with some childhood friends, strumming Indian pop music on the guitar. However, to master the Sitar, Kenny needed to go deeper.

“He realised that he needed to live with the Indians and fully understand them before he can develop the bhava or expression in his music,” says Chandra Sekaran, 57, Kenny’s best friend and tabla accompanist.

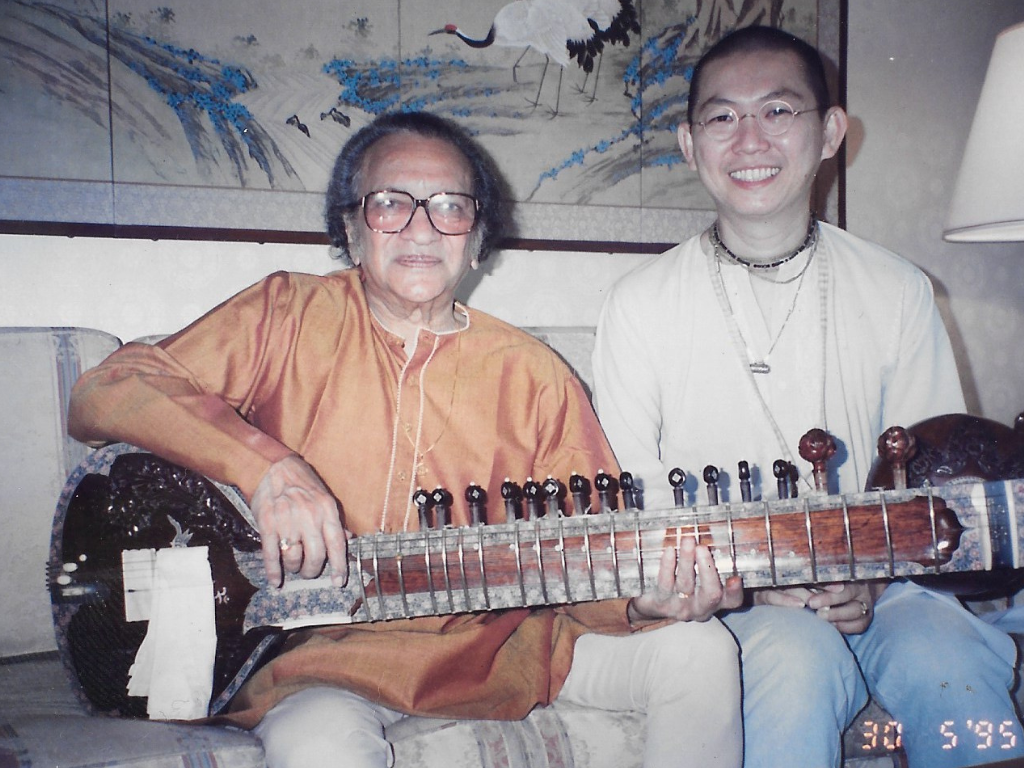

He persisted, learning the instrument and travelling to India, until he was introduced to N.R. Rama Rao, one of Shankar’s earliest disciples. After three years, Rama Rao deemed him worthy of meeting Shankar. Kenny finally met his future guru in 1994.

“He realised that he needed to live with the Indians and fully understand them before he can develop the bhava or expression in his music,” says Chandra Sekaran, 57, Kenny’s best friend and tabla accompanist.

He persisted, learning the instrument and travelling to India, until he was introduced to N.R. Rama Rao, one of Shankar’s earliest disciples. After three years, Rama Rao deemed him worthy of meeting Shankar. Kenny finally met his future guru in 1994.

Kenny with his guru, the sitar legend Ravi Shankar in 1995. Image credit: Kenny Tan

For the love of music, and the love of his sons

Kenny also wanted to give the gift of music to his sons, who both took up Indian music at a young age. From the time they were toddlers, Kenny would spend at least three hours a day tutoring Krsna and Govin.Krsna, now 33, plays the Sitar, while Govin, 30, learnt the Tabla from Chandra. Being fixtures in Singapore’s Indian classical music scene, the brothers have won numerous awards and performed around the world.

A 2016 Tamil Murasu article featuring Govin, Krishna and Kenny playing the tabla and sitar together. Image credit: Kenny Tan

As the two sons performed for Kaya in the living room, their many years of practice was evident, as was their ability to communicate while they play.

During the school holidays, the family would travel to India to further their knowledge. Govin says the trips showed him that music is about relationships as well as skill. That’s particularly true of Indian music, which is often taught through a master and disciple relationship.

“Indian music is taught completely by word-of-mouth. The sitar can achieve many different tones, depending on how the teacher sings it, which is impossible to record on paper,” Kenny says.

Because of the improvisational nature of Indian music, the synergy between the sitar player and his accompanist has to be strong. That was why Kenny enlisted the help of Chandra, his trusted tabla player, to be Govin’s first tutor at 12 years old. Krsna picked up his first sitar when he was three. By the time he was 12, he was so accomplished that he came first in the Classical Indian Music Competition for Sitar under the open category in Singapore.

During the school holidays, the family would travel to India to further their knowledge. Govin says the trips showed him that music is about relationships as well as skill. That’s particularly true of Indian music, which is often taught through a master and disciple relationship.

“Indian music is taught completely by word-of-mouth. The sitar can achieve many different tones, depending on how the teacher sings it, which is impossible to record on paper,” Kenny says.

Because of the improvisational nature of Indian music, the synergy between the sitar player and his accompanist has to be strong. That was why Kenny enlisted the help of Chandra, his trusted tabla player, to be Govin’s first tutor at 12 years old. Krsna picked up his first sitar when he was three. By the time he was 12, he was so accomplished that he came first in the Classical Indian Music Competition for Sitar under the open category in Singapore.

Govin and Krsna Tan have been playing Indian classical music since they were children.

“Sitar is quite a difficult instrument to learn. It’s also because we did not have YouTube or that much access to the different sitar sounds back in the 90s. Everything my dad sings is whatever I play,” Krsna says.

“I make an effort to deliberately learn about another culture. (When I didn’t) understand the Indians, I go there, sit with them and eat with them. If you live with them and understand them, you will definitely not even feel that you are Chinese or Indian,” he says.

His sons feel the same way. For decades now, they have been playing at temples and festivals, where they have found receptive and friendly audiences.

A connection to other cultures

For Kenny, music is not just a passion. It’s also a great way to truly understand a person’s culture and way of life.“I make an effort to deliberately learn about another culture. (When I didn’t) understand the Indians, I go there, sit with them and eat with them. If you live with them and understand them, you will definitely not even feel that you are Chinese or Indian,” he says.

His sons feel the same way. For decades now, they have been playing at temples and festivals, where they have found receptive and friendly audiences.

When we played (at the temple) the first few times, they were very encouraging. Never once have they said we were not good enough. It’s always a good job or let me teach you something new today.

For the Tan brothers, music crosses boundaries, binds them to others, and fosters community. That’s true regardless of the type of music.

“Be it a heavy metal concert with head bangers or a classical music concert, people show respect to their environments and behave collectively as one. That’s healthy social behaviour,” Krsna says.

“Be it a heavy metal concert with head bangers or a classical music concert, people show respect to their environments and behave collectively as one. That’s healthy social behaviour,” Krsna says.

Watch a short segment of our session with Kenny, Krsna and Govin ft. Uncle Chandra:

.jpg?la=en&h=262&w=393&mw=393&hash=1E254EA2A0E06C0A259CC699919DDA6F)