Bolstering the Banjarese heritage

They might be the smallest ethnic Malay group in Singapore, but the island's Banjarese community are staying rooted to their rich heritage through language, culture and food.

- 5 Jul 2022

Syafiq wears the Babaju Kubaya Panjang, a traditional Banjarese costume usually worn by Banjar royalty.

Using his left index finger and thumb, Syafiq Sahrom gently picks up his mother’s wedding ring and peers intently through its shank, as if gazing into a parallel world visible only to him.

With its intricate handiwork and impeccable gold finish, the ornament is an ode to a bygone era of jewellery making where it was man, not a machine that weaved magic.

“It is one thing to listen to stories of the past but it is another feeling altogether when you get to hold a piece of history in your hands. It just makes it that much more real, you know?” whispers the 23-year-old, without looking away.

For Syafiq, this ring is more than just a family heirloom. It is a portal into his Banjarese heritage.

With its intricate handiwork and impeccable gold finish, the ornament is an ode to a bygone era of jewellery making where it was man, not a machine that weaved magic.

“It is one thing to listen to stories of the past but it is another feeling altogether when you get to hold a piece of history in your hands. It just makes it that much more real, you know?” whispers the 23-year-old, without looking away.

For Syafiq, this ring is more than just a family heirloom. It is a portal into his Banjarese heritage.

Photo of Syafiq’s mother’s wedding ring which was crafted by renowned Banjarese diamond trader and jeweller Haji Ahmad Jamal bin Haji Mohd Hassan.

In the early 1940s, his late grand uncle Haji Ahmad Jamal bin Haji Mohd Hassan had established himself as one of the leading diamond traders and jewellers — a profession synonymous with early Banjarese settlers — in Singapore. Despite his prominence, a declining artisan diamond trade driven by the emergence of mass market jewellery brands meant that he had to give up his craft by the late 1980s.

But not before completing his last commissioned work in 1989 — a matrimonial ring for his nephew’s bride-to-be, Syafiq’s mother. Underscoring the significance of Haji Ahmad Jamal’s last masterpiece is the fact that its recipient was not even from the Banjarese community. In fact, she is “Chindian” — a descendant of both Indian and Chinese ancestry.

“I think what makes this ring more beautiful is the fact that my mum is not from the Banjar community. This openness and willingness to embrace different cultures and races pretty much sum up what it means to be Banjarese,” he says.

Despite being the smallest ethnic Malay community in Singapore, the Banjarese diaspora continues to grow in an increasingly modernised society through a sense of community togetherness, language and food.

The peace and stability that Singapore provided was also a refuge for many Banjar families who had to leave South Kalimantan due to the Banjarmasin War. This marked an influx of several Banjar families who began to settle in Singapore by the late 1800s and early 1900s. Renowned for their diamond trade in the 19th and 20th centuries, many early Banjarese plied their trade in Kampong Intan, an area located within the vicinity of Kampong Gelam. Today, Kampong Intan is undefined in size, but includes the stretch of road known as Jalan Pisang.

But not before completing his last commissioned work in 1989 — a matrimonial ring for his nephew’s bride-to-be, Syafiq’s mother. Underscoring the significance of Haji Ahmad Jamal’s last masterpiece is the fact that its recipient was not even from the Banjarese community. In fact, she is “Chindian” — a descendant of both Indian and Chinese ancestry.

“I think what makes this ring more beautiful is the fact that my mum is not from the Banjar community. This openness and willingness to embrace different cultures and races pretty much sum up what it means to be Banjarese,” he says.

Despite being the smallest ethnic Malay community in Singapore, the Banjarese diaspora continues to grow in an increasingly modernised society through a sense of community togetherness, language and food.

Early beginnings: The arrival of the first Banjarese in Singapore

Hailing mostly from South Kalimantan, a province of Indonesia, Singapore’s Banjarese community can trace their lineage as far back as 1824, when Dutch vessels from the capital of Banjarmasin began to arrive on Singapore’s shores. After decades of Dutch monopoly, Indonesia had finally become a free port. This meant better business prospects and a chance to build a new life in Singapore’s booming port industry.The peace and stability that Singapore provided was also a refuge for many Banjar families who had to leave South Kalimantan due to the Banjarmasin War. This marked an influx of several Banjar families who began to settle in Singapore by the late 1800s and early 1900s. Renowned for their diamond trade in the 19th and 20th centuries, many early Banjarese plied their trade in Kampong Intan, an area located within the vicinity of Kampong Gelam. Today, Kampong Intan is undefined in size, but includes the stretch of road known as Jalan Pisang.

A selection of gem and diamond weighing tools belonging to Haji Ahmad Jamal bin Haji Mohd Hassan.

According to a 1921 census, there were 377 Banjarese in Singapore. Yet, despite the relatively small numbers when compared to other Malay ethnic groups like the Bugis or Bawean communities, the Banjar community has always prided itself on its sense of unity and cohesiveness.

As Suhaili Osman, curator for the Banjar exhibition at Malay Heritage Centre (MHC) explains, one way that the community ensured longevity in the past was by marrying within themselves. This took place either when two separate Banjarese families decided to marry their children to each other or when members of the community got married to their immediate or distant cousins. The existence of this practice was also confirmed by 58-year-old Faridah Jamal — Syafiq’s paternal aunt and daughter of Haji Ahmad Jamal — who got to know about the custom through recollections by her mother.

As a result, most people from the present-day Banjar community can easily identify one another as members of the same family tree. This is done by recognising familiar names or by linking ties through mutual relatives.

While the practice of marrying within the community has long been discontinued, its impact is still felt today.

“Marrying within the community was one of the ways that the Banjarese protected their cultural heritage and identity. Their numbers might be small, but most of the urban families know one another – that is a trait unique to the community.”

As Suhaili Osman, curator for the Banjar exhibition at Malay Heritage Centre (MHC) explains, one way that the community ensured longevity in the past was by marrying within themselves. This took place either when two separate Banjarese families decided to marry their children to each other or when members of the community got married to their immediate or distant cousins. The existence of this practice was also confirmed by 58-year-old Faridah Jamal — Syafiq’s paternal aunt and daughter of Haji Ahmad Jamal — who got to know about the custom through recollections by her mother.

As a result, most people from the present-day Banjar community can easily identify one another as members of the same family tree. This is done by recognising familiar names or by linking ties through mutual relatives.

While the practice of marrying within the community has long been discontinued, its impact is still felt today.

“Marrying within the community was one of the ways that the Banjarese protected their cultural heritage and identity. Their numbers might be small, but most of the urban families know one another – that is a trait unique to the community.”

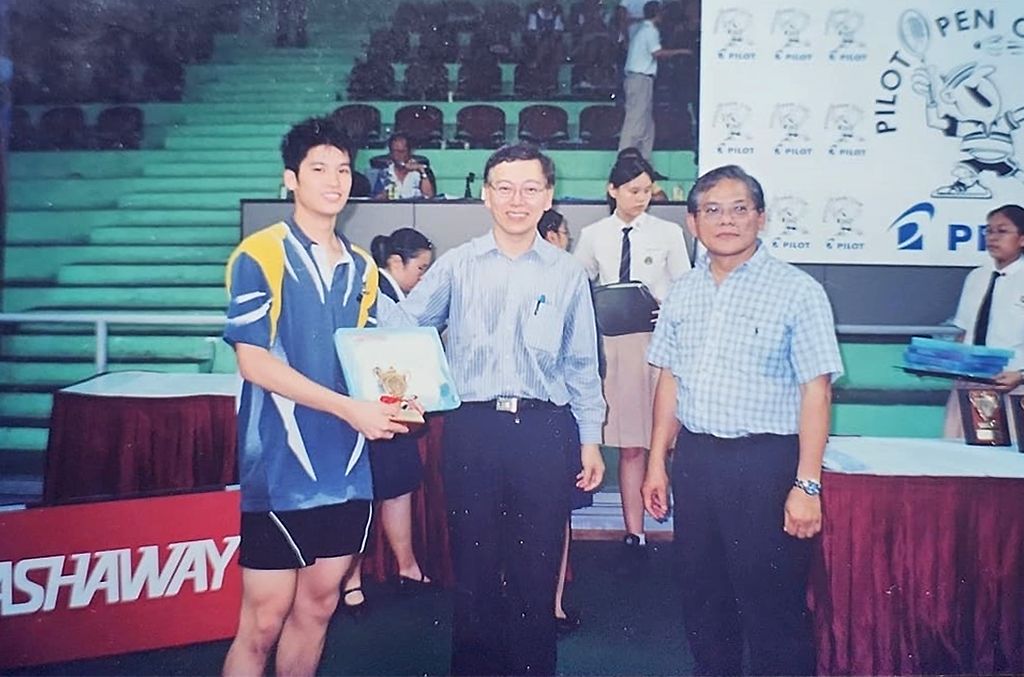

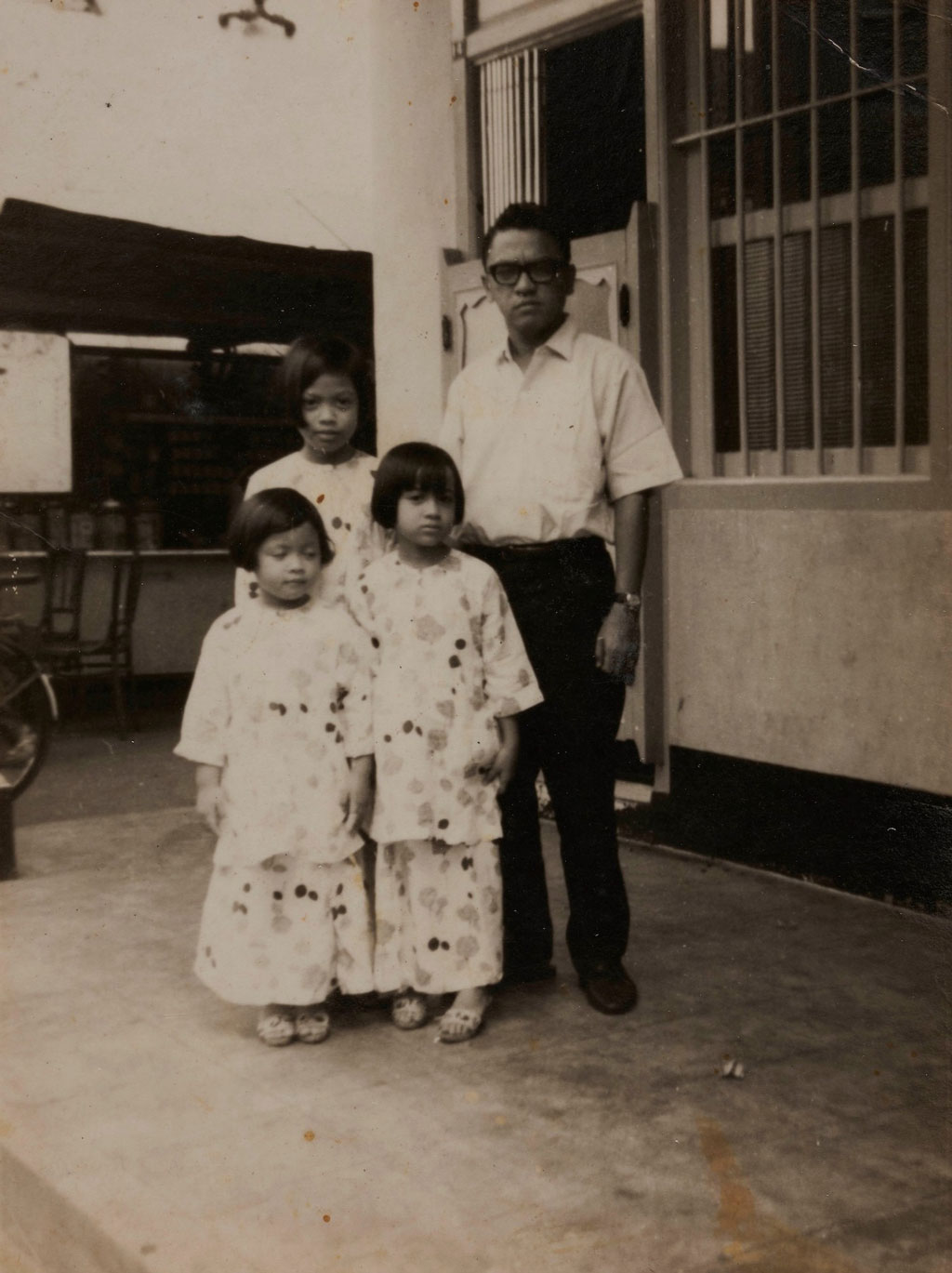

Faridah Jamal (standing in front on the extreme left) poses for a family photo with her siblings and father (extreme right) Haji Ahmad Jamal Bin Haji Mohd Hassan. Photo credit: Faridah Jamal.

Basa Banjar: The language of the Banjar community

Steely confidence surges through Syafiq’s voice as he recites his favourite Basa Banjar (Banjar language) idiom aloud. “Haram manyarah waja sampai kaputing”, he exclaims thunderously, his eyes glistening with pride.Translated into English as “Let not the steel (of a blade) stop short until its very point”, the adage serves as a reminder for the Banjarese community to undertake all endeavours with determination. Most importantly, it reminds them to never give up.

Similarly, the same can be said about his attempt to learn the Banjarese language.

While Syafiq's father has minimal proficiency of the dialect, work and family commitments at the time meant that he could not pass on the love of the language to his children. Beyond this, there was also the issue of being practical: Bahasa Melayu was the examinable language in school, not Basa Banjar.

"In a sense, I am thankful that I was exposed to Basa Banjar due to my interest in my heritage. Before this point, like many other youths from the community, I was taught Bahasa Melayu due to the fact that we had to take it as a second language in school."

Despite not being introduced to the language, he made an attempt in 2018 to learn Basa Banjar by joining free weekly classes conducted by Haji Abdul Latiff bin Omar, a senior member of the community and strong advocate of Banjar heritage. Held at Siglap Community Centre, the classes were a way for him to understand the rich literature and linguistic traits.

But when the pandemic struck in February 2020, lessons were suspended indefinitely as a safety precaution. Despite not being able to attend classes for a period of time, Syafiq refused to give up. He regularly revises his class notes and re-read key passages in an attempt to stay in touch.

“I’ve always believed that languages are an important portal into the past so learning Basa Banjar means I get the opportunity to fully understand my culture and the way my ancestors viewed the world. In a way, it allows me to connect directly with them,” he says.

Despite its declining use locally, Basa Banjar provides the community with a sense of familiarity and remains an important identity marker across generations. They also help the community connect with relatives from other places in the region like Batu Pahat in Malaysia and Pontianak in Indonesia.

As Syafiq explains, one of the key differences between Bahasa Melayu and Basa Banjar is the number of vowels used. The Malay language uses five vowels; A, E, I, O, U while the Banjarese language only uses three vowels; A, I, and U.

For example, "me" in English is translated into "saya" in Malay and "ulun" in Basa Banjar.

| Basa Banjar | Bahasa Melayu | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Ulun | Saya | Me |

| Ikam | Awak/Kamu | You |

| Bulik |

Balik |

To return |

| Sabalum |

Sebelum | Before |

| Basura | Berbual | To converse or narrate |

Common words that illustrate the linguistic differences between Bahasa Melayu and Basa Banjar.

For Faridah, the decline of the use of the Banjarese language signals a shift in the community’s identity. “We were not formally taught to speak the language but we were familiar with certain aspects of the language.”

These include everyday words like "intaluk" (egg) and "gawi" (work). Other common phrases include "Ikam mau kamanak?" (Where are you going?) or "Ayuhak!" (Let's go!").

“As a foodie myself, I’m always curious about the origins of dishes and how they came to be. Understanding Banjar cuisine allows me to taste flavours of the past and appreciate the intricacies of how they are prepared,” he says.

These days, he makes it a point to carry on the tradition of recreating traditional Banjarese cooking by following recipes passed on from his grandparents and relatives.

His favourite dish to cook? Wadai Kiping. Translated into English as “flattened food", it comprises of sweet glutinous rice pellets. A staple of Banjarese cuisine, it is a sought-after dish at family gatherings and community get-togethers.

For Faridah, the decline of the use of the Banjarese language signals a shift in the community’s identity. “We were not formally taught to speak the language but we were familiar with certain aspects of the language.”

These include everyday words like "intaluk" (egg) and "gawi" (work). Other common phrases include "Ikam mau kamanak?" (Where are you going?) or "Ayuhak!" (Let's go!").

Food for thought

Where language is a work in progress for Syafiq, food has always been the most natural way of connecting with his Banjarese culture.“As a foodie myself, I’m always curious about the origins of dishes and how they came to be. Understanding Banjar cuisine allows me to taste flavours of the past and appreciate the intricacies of how they are prepared,” he says.

These days, he makes it a point to carry on the tradition of recreating traditional Banjarese cooking by following recipes passed on from his grandparents and relatives.

His favourite dish to cook? Wadai Kiping. Translated into English as “flattened food", it comprises of sweet glutinous rice pellets. A staple of Banjarese cuisine, it is a sought-after dish at family gatherings and community get-togethers.

Syafiq uses his palms to mould the glutinous rice pellets as he cooks the Wadai Kiping dish.

Despite the rarity of finding the dessert these days, he remains determined to safeguard the culinary identity of the Banjarese community.

“Following the specific instructions of the Banjarese version helps me reaffirm my identity as a member of the community,” he says. “It is almost a way of saying ‘This is me, this is who I am’.”

“Following the specific instructions of the Banjarese version helps me reaffirm my identity as a member of the community,” he says. “It is almost a way of saying ‘This is me, this is who I am’.”

A hearty plate of Wadai Kiping prepared by Syafiq with assistance from his mother.

From safeguarding the language of the Banjar community to retaining its gastronomic specialities, Syafiq is confident that the essence of what it means to be Banjarese will always be a key part of his identity.

“It doesn’t matter what tomorrow brings. As long as I am alive, I will carry the honour of being Banjarese.”

“It doesn’t matter what tomorrow brings. As long as I am alive, I will carry the honour of being Banjarese.”